==========================================================================================

May 2025

Influence of the Round Britain Race on Trimaran acceptance

Before the Round Britain Race came to be, there were a couple of major races across the Atlantic, so lets start the story there.

In 1954, I was building small single-handed International ‘Flying Moths’ in Netley, Hants UK. Sadly unknown to me at the time, another single-hander was being built less than 15 miles away in Portsmouth. This was JESTER, the 25ft Folkboat hull with a fully enclosed cabin, that was to compete in the first 1960 singlehanded race across the Atlantic. (Later to be called the OSTAR).

Both the race and the boat were products of the inventive mind of Blondie Hasler. ‘Blondie’ was retired from the Royal Marines after an exciting life of many daring wartime adventures .. including the wartime sinking of German ships in Bordeaux harbor, by setting mines from inflatable kayaks .. a story later immortalized in a film called “The Cockleshell Heroes” All his life, Blondie relied on no one but himself so JESTER was ‘set up to survive above all else’. Speed was secondary but 'keep going' was prime. She had a simple unstayed junk-rig that could readily be reefed in minutes and with only that one sail, there were never any sail changes. She had a fully enclosed cabin (like a self-righting lifeboat) and was steered by a self-steering rig he designed & built himself.

Although trimarans were already being ocean-sailed by a few enthusiasts, the yachting world as a whole thought they were 'freak boats, only good for harbor parties', not for an ocean, so they were often barred from races. Even inventor Blondie was not convinced they could cross the Atlantic from East to West against head winds. Although multis were reluctantly permitted, only 4 monos finally crossed the start line for that first 1960 OSTAR, as the one trimaran entered, failed to show up. JESTER however made several trips across the pond, surviving several knock downs, but was finally sunk after a breaking wave smashed in her coach-roof. A new Jester was made using cold-molding, and continued to make numerous safe ocean voyages. Although she was not fast by todays' standard and could not sail close-winded, her large traditional keel helped keep leeway down. Here is some more history if she interests you: https://jesterchallenge.org

But the gauntlet was now down and the time came to test out multihulls in tough ocean conditions. Blondie himself also proposed a single-handed race around the British Isles but as there were many physical hazards, better judgment kicked in, so when this first Round Britain Race (RBR) was finally run in 1966, it was required to be sailed with a co-skipper

Repeated typically every 4 years, a look at the entrants and how trimarans performed is like 'a time capsule on trimaran development' and there is no doubt that the challenges the RBR presented, have made for increasingly faster and more seaworthy multihull designs. So follow along as I briefly summarize each RB race from 1966-1985, to see how and why, trimarans now  hold more ocean racing records than any other boat type.

hold more ocean racing records than any other boat type.

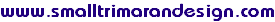

When we think of ‘Sailing Round Britain' we may first think of "harbour hopping" around Britain. In reality, it's far from that. It's 2000 miles of potentially some of the roughest water on the planet. Just the first leg is daunting, as it's like doing the first half of the gruelling Fastnet Race across the often intimidating Irish Sea. Then the first stopover at Crosshaven, which later moved west to Galway. For all the races summarized here, mandatory stopovers were 48 hours, to ensure some rest and a chance to do repairs. The minimum boat length accepted was 25ft, with typically no upper limit, so 7 classes evolved from 25 to 75ft.

Since its inception in 1966 this race has shown the sailing world what a well designed multihull is capable of. Although there were only 16 entries in that first race, the first 6 places went to 3 trimarans & 3 catamarans. As only 10 boats finished, the last 4 were monohulls, finishing 5 to 10 days behind the first trimaran. It was perhaps the first real shock to the traditional world of monohulls, that perhaps multis were not as unseaworthy or slow upwind as many were saying! That 1966 race was won by a truly amazing 42ft trimaran called TORIA that was WAY ahead of its time in both design & build. Designed and sailed by the then young designer Derek Kelsall, she was also the first ever composite trimaran, built using PVC foam and polyester resin .. a combination that Derek stayed with all his long life. Derek & I became email friends during his last 10 active years and I am still in awe as to what he achieved .. also building the largest composite catamaran (then 45ft) and eventually the largest foam-cored monohull at that time (80ft!) after first training a group of Marines to do the work. That boat .. Great Britain ll … WON its first Whitbread (around the world) race and went on to participate in at least 4 more. (If you want to read more about Derek’s amazing early exploits, see my 2010 Interview with him

Derek finished that nearly 2000 mile race 16 hours ahead of a new Cat by the Prout Brothers called SnowGoose that would soon be in production. (Based on the smaller Endeavour, she had semi-circular hulls giving low frictional drag up to around 10k, though capable of speeds in the mid teens.

The surprising results spread quickly, so for the next Round Britain race in 1970, 13 multis turned up to race against 12 monos, though the mono enthusiasts would not be outdone. They decided “bigger is better” and took first place with a 71ft mono, the only mono mind you in the first 6 finishers. The Snowgoose cat again finished 2nd with a new 44ft trimaran called Trumpeter in 3rd (another Kelsall design, this time created for the American Phil Weld).

Finally, designers had found ways to make multis more seaworthy and with a very acceptable upwind performance that helped them to finally perform better than monohulls overall. Sailors were also learning of the differences in handling and sailing too, so that factored in to their fine results

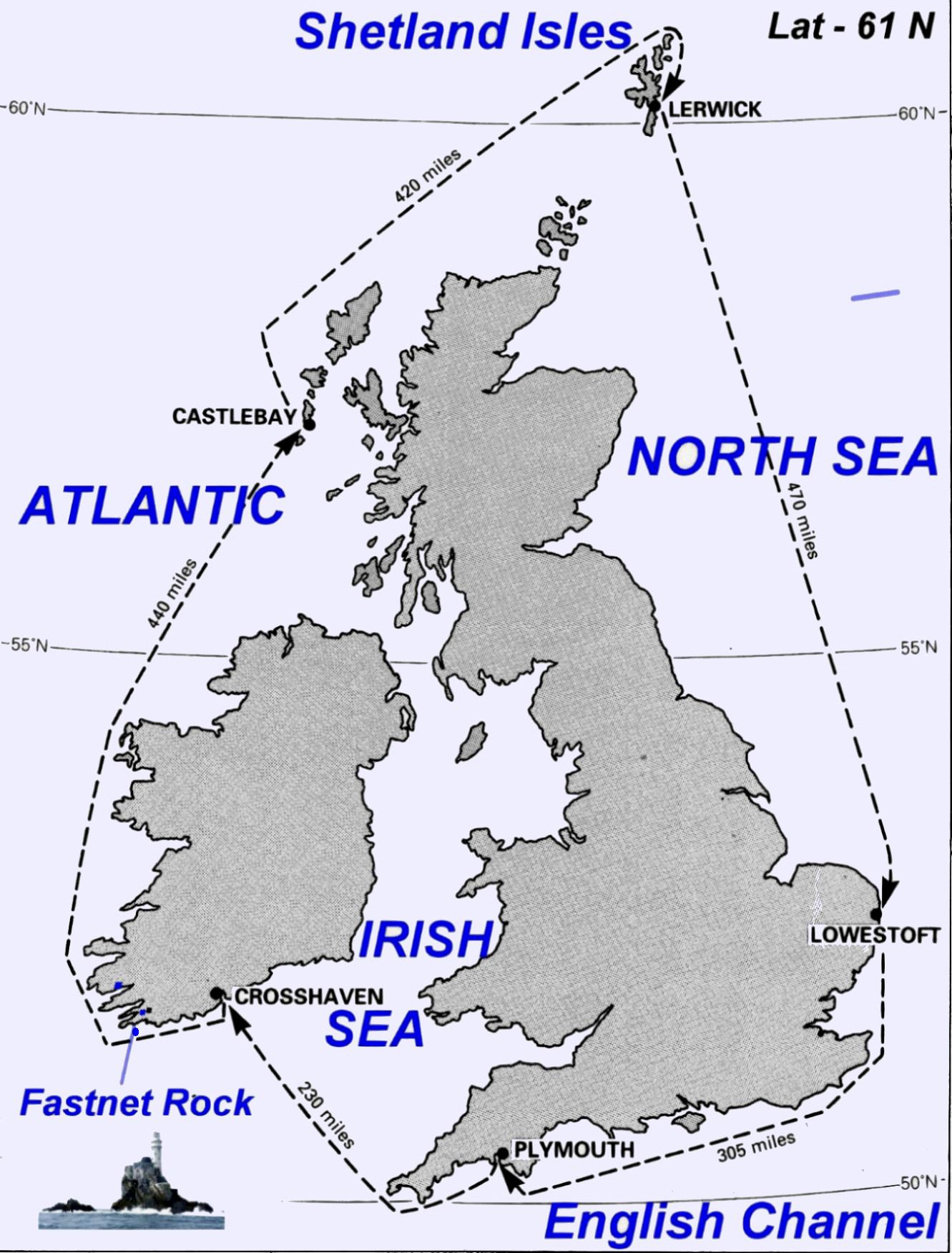

In the 3rd race (1974) there were now 61 starters with 5 of the first top finishers being trimarans, with the monster 70ft Cat British Oxygen taking 1st, followed by Mike McMullen in the 46ft Newick  Tri Three Cheers,

Tri Three Cheers,  amazingly only 1 hour behind and

amazingly only 1 hour behind and

still a couple of hours ahead of a 60ft trimaran called Gulf Streamer. It must have been a rough year as 21 boats retired early ... with no one boat- type showing worse than the others.

While the main thrust of this article is to show how this particular event has shaped and show-cased trimarans over the years, each event has many individual stories that make fascinating reading … more on this later. One ‘learning experience’ was from a venture into folding/demountable trimarans by 505 designer John Westell. He had designed a 46 footer and entered the 1974 Round Britain race. He was coming home down the North Sea in about 9th place (out of 61 starters) in very ‘lumpy” conditions when a float (ama) broke off and drifted away (!). Although they could balance the boat like a Proa, they could not risk to tack, so finally John & crew had to 'abandon-ship'. Later the boat was towed by the CG into a UK harbor but the lost float turned up near Stavanger, Norway! So the interaction of a windward ama with breaking waves cannot be ignored ! (another reason I use asymmetrical amas on the W17 ;)

Another story from the same event featured the tenacious Mike McMullen of Three Cheers fame. Racing at speed in 2nd place, Mike went forward to change a headsail in lumpy conditions and was literally thrown overboard. Although he grabbed a lifeline, the boat was moving too fast and he could not hold on. The boat then sailed over him, reportedly nearly breaking his leg. He was fully clothed in storm gear so ‘weighed a ton’, but finally surfaced about 50m from the boat that his crew had meanwhile managed to stall, head-to-wind. Slowly the boat drifted back to Mike and he managed to grab the boat. But there was no way he could climb aboard especially with the boat continually surging forward and upward. So with Mike struggling to hang on, co-skipper Martin managed to lower all the sails to tame things down … but they still had to get Mike on board. Finally, they used a halyard and Martin managed to winch him aboard. Whew, that was close! Being as they finished only 1hr 11 mins after the 60ft Gulf Streamer, its possible they might have created a photo-finish without this scary event. Newick’s Three Cheers design was indeed a fast boat **

(Sadly Mike was thrown an even more extreme challenge just 2 years later. While preparing Three Cheers to enter the 1976 Singlehanded race across the Atlantic, his wife Lizzie was helping him by polishing the hull. After accidentally dropping the electric polisher in the shallow water, she did what many might have done; she grabbed the unit to rescue it. Tragically, she was killed instantly and as one might expect, Mike went into shock and deep grief himself. What went through his mind we will never know, but he decided to still enter the race that started just 2 days later. But not far west of Ireland, both he and Three Cheers disappeared, never to be seen again …. though a piece with Nav. instruments from the boat was reportedly dredged up some years later off Iceland. A truly tragic moment in time, that must still haunt many today.

In permanent memory of them both, there is now a special trophy (silver replica of the famous Newick tri) carrying the name of 'Lizzie McMullen' and awarded to the first Multihull to finish in the cross Atlantic Race, so going to 32ft Third Turtle (Canadian Mike Burch) in 1976, and to the 50ft Moxie sailed by US Phil Weld in 1980

.

.

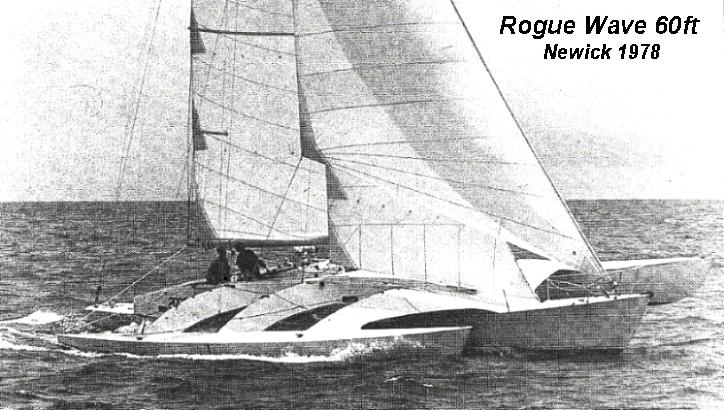

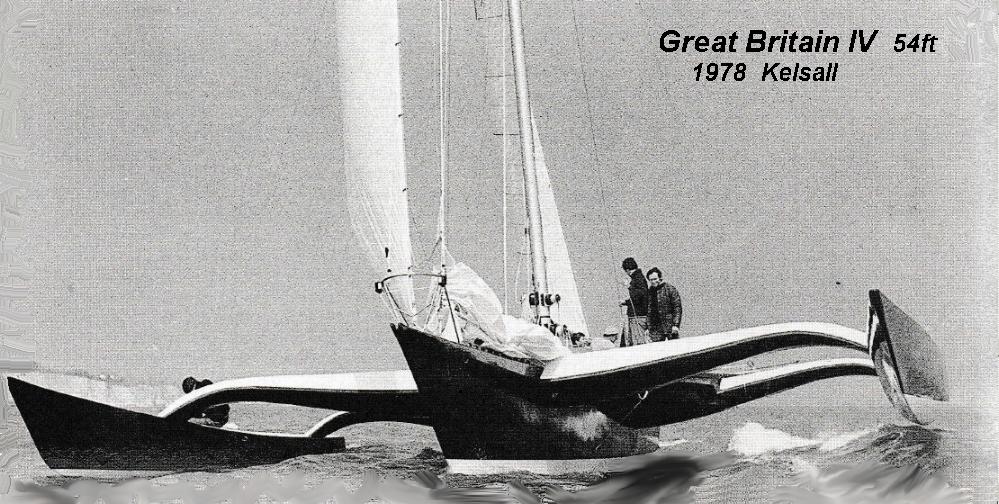

By 1978, things were getting very competitive for the RBR. There was now no doubt that a trimaran could win this tough 2000 mile challenge, so all the designers were pitching in with their best concepts and the resulting boats were amazing for the time, now nearly 50 years ago! Again, Derek Kelsall designed  another winner with his 54ft

another winner with his 54ft  Great

Great

.

Britain lV. Nick Keig’s 53ft Three Legs of Mann (which I believe Derek-K also had a hand in), was 12.5 hrs behind, with Dick Newick’s 60ft Rogue Wave in 3rd, just another hour behind after 13 (21-8) days of racing. 8 of the first 10 boats were trimarans and the first cat was a 32ft Comanche production boat in 19th, 3 days behind the leading tris.

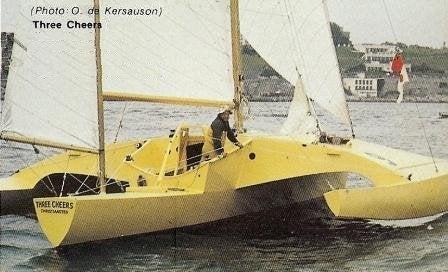

One outstanding race was by the US designer/builder Walter Greene who sailed his 35ft A Cappela with his wife Joan, to a 4th place overall, only 22 hours behind the much larger Rogue Wave. Just 10 hrs behind A Cappela was Nigel Irens in his even smaller Newick VAL tri of 31.5ft. (see foto above)

Walter Greene designs are not so well known in Europe but always interested me as they matched my own thinking in these ways..... ‘sides nearly straight & vertical, simple but surprisingly efficient forms’. They were often simply built in plywood, even if built professionally in a Maine boatyard. In fact the largest multi I ever sailed was a 62ft Walter Greene cat … and she still had tillers P&S. (It seemed effortless for the boat to hit the high teens …. as it certainly would be for a 60’ W17 ;)

Walter Greene designs are not so well known in Europe but always interested me as they matched my own thinking in these ways..... ‘sides nearly straight & vertical, simple but surprisingly efficient forms’. They were often simply built in plywood, even if built professionally in a Maine boatyard. In fact the largest multi I ever sailed was a 62ft Walter Greene cat … and she still had tillers P&S. (It seemed effortless for the boat to hit the high teens …. as it certainly would be for a 60’ W17 ;)

The increasing popularity and success of trimarans hit a peak for the 1982 race. First there were a record 85 entries!

Only 1 of the first 16 boats was a monohull and she was 60ft and finished 12th. The first 9 to finish (34-65ft) were ALL trimarans. Impressive to me is that Walter & Joan Greene were back in their 35ft A-Cappela, finishing 8th and first in Class. The previous success of the Greene’s in 1978 must have motivated others as there were now at least 6 husband/wife teams in 1982, with 3 more entries sailed by all-female couples, so ‘hats off to the ladies’. Perhaps even more impressive was that the winning trimaran was a 60ft trimaran also sailed by a couple, Rob James and his wife Naomi. (Mind you, Naomi was a tiger amongst female sailors, even racing solo across the Atlantic competing against her husband in 50+ foot monos).

The last Round Britain Race that I will briefly review was in 1985. With 40kt gales, it was one of the toughest, with even good sails getting blown out and with 23 of the 74 starters retiring and 3 boats dismasted. One of the scariest accidents was a 45ft catamaran (likely a Spindrift) that was in 11th place on the last leg, when it was run down at night in the English Channel by a Dutch coaster and sunk. The crew were thankfully picked up ..., one being the famous Aussie designer, Lock Crowther! Despite the challenges, this was a race that several small boats survived to the finish and earned much respect, including 5 at the lower end, under 27ft.

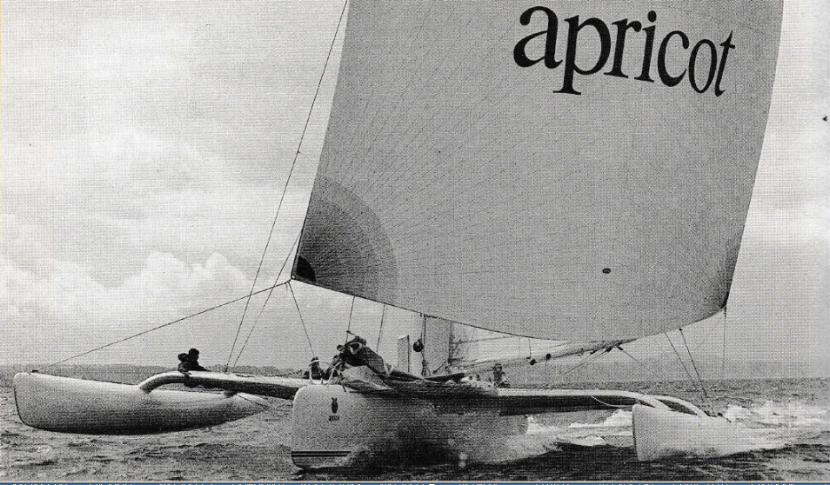

By 1985, the upwind ability of trimarans even in rough conditions, had been notched up to something only dreamed about a decade earlier. At the finish of this race, magnificent ‘triple-hulled machines’ held 12 of the top 20 places, including the prized top 3. Although most boats suffered some effect of the strong wind conditions, the impressive 60ft Apricot, crewed by its designer Nigel Irens, had a close battle with another 60ft Tri called Paragon until the latter developed structural  damage

damage

.

between the 3rd & 4th stopover and had to retire. After that, Apricot flew home with a 17 hour lead over Morr-Energy, with Marlow Ropes (ex Umupro Jardin) only minutes behind. All were Class 2 (60ft) Tris. The first Class 1 boat was a classic 75ft Peter Spronk catamaran finishing 8th overall. 9th and 10th went to two much smaller trimarans (35ft) about 2 days behind Apricot. The 2nd of these is interesting as it was the 35ft QuickStep, an early tri by the Quorning family and sailed by a young Jens Quorning, who now owns & directs Quorning Boats. Erik Quorning sailed the smaller ‘first Dragonfly’ sponsored by Hempel Paints so called “Magic Hempel”. Only 25ft long, she astonished many hardened sailors as she finished 18th overall, with the next boat of her size back in 33rd ! Timed at 25.4 kts in the North Sea, she was awarded the Boxall Trophy for the fastest boat for her WL Length. She was the start of todays fleet of impressive Dragonfly's and at 1 kt per foot of length, arguably outperformed them all. Simple, demountable, light yet strong and good looking.

Magic Hempel had proved herself for Dragonfly Boats and was soon bought by a sailing doctor in New York, where she won every race she entered. Well, with one 'variation'. That exception was to race to the aid of a 65 yr old skipper hanging on to the stern of his sinking mono in Long Island Sound after being ‘run through’ by a steel fishing vessel who failed to stop during a dark early morning. Soon 'sold' on the general design and quality, 'the Doc' upgraded to a larger DF while Magic Hempel was sold to the Pacific North West where she was entered in the Swiftsure Race. Initially rigged as light as possible, an undersized waterstay failed and MH was wrecked on a shore. Although the mainhull was holed by either the broken aka or the mast, the wrecked boat was rescued and bought by Kurt Hughes who designed replacement amas for her, patched up the damage, welded up the forward aka beam (now 2" short), and had a new mainsail made. [That shortened aka on one side 'accidentally' created ama tow-in, so since measuring that MH sailed closer on that tack, I have designed in a little 'toe-in' on all my tri designs ever since]. Soon she was back on the East Coast, so frightening her new owners by her sudden acceleration, that they were happy to sell her. Guess who the lucky buyer was? Me ;) I doubt the sellers even knew her earlier history as the new amas lacked all her original decals. I set about cleaning things up inside and having new decals made and then checked back with the Quornings to say she was now back in good hands. I then had 16 great seasons with her, all in freshwater, but after several new owners, again she has new & even better amas, new sails, new cabin top and motor. She is now back in salt water in Nova Scotia, Canada. But the Dragonfly design success grew out of that first success at the 1985 Round Britain Race ... and my own slightly smaller and lighter W22 owes some of her ancestry and fine performance to Magic Hempel also. Since 1985, (also the intro year of the F27), there is no excuse for a trimaran to not perform upwind on par with the best monos out there. They may still not point as high (due in my view to windage more than the hull format), but with up to 50% more speed, they can reach upwind points just as fast if their rig is efficient and well trimmed, and blow any non-foiling mono away once reaching 60-150 degrees off the wind.

Well, that completes my very brief review, up until I was personally touched by the event through my purchase of Magic Hempel. Eight or nine more Round Britain Races have been held since, so perhaps this will raise special interest in this event, to see what is coming to us via future RPR successes.

Mike ... May 2025

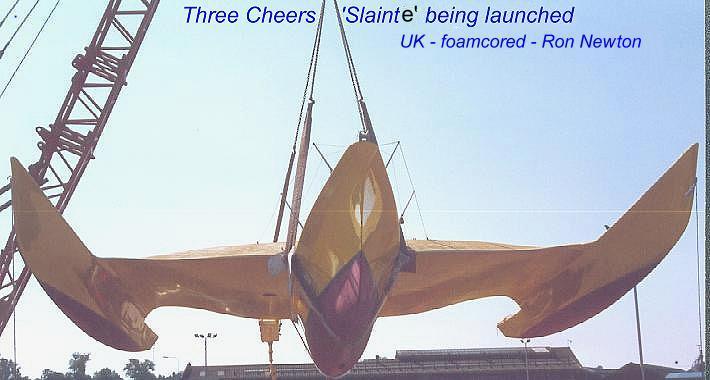

** Re: Three Cheers. In 2021, I received an order for W17 plans (C168) and as I am always interested in what new W17 builders have sailed before, I discovered that this retired dentist in the UK had actually built a near replica of Three Cheers, using the latest composites of the time. In consultation with Dick Newick, he simplified the rig to a sloop rig and increased the overall beam by 2ft but kept the simple interior, as it was light and totally adequate for his mostly singlehanded sailing. Dick even paid him a visit and complimented him on his fine work. Once complete, the owner went on to make about 5 seasonal circumnavigations of the British Isles .. mostly with a dog (or two) as his companion. As he was also in Cruising Mode, he got to know many fun harbors over the years. So in 2020, fast approaching 80, he decided it would soon be time to downsize, so after checking out what there was, zoned in on a W17 that would be built with a plywood main hull, but with composite amas and akas (beams) to lower its weight. Once finished, he plans to return to his favorite harbors with the W17 in tow, and then sail-camp-cruise locally to explore what he missed because his Newick 46 was too big.

Once the W17 is ready to sail or even before, this impressive Newick 46 will be For Sale and it will be a wonderful boat for anyone dreaming to do what owner Ron had done in his younger days. Write me if you have any interest before its taken .... these Classics are becoming very rare and this one (named 'Slainte', Celtic for Cheers) is a fine example. As Andre and I were in the UK Spring 2024, we had a tour of the boat so we can report she is simple and basic, but Ron kept her light & strong with high quality workmanship, and with the potential to perform at least as well as the original Three Cheers. For me it is an honor to know that Ron selected to build a W17 after owning such a boat... as he knows just what works for a performance, vice-free trimaran. He says he is also eager to build & experience the carbon-fiber Waters WingMast (Mk.l).

Once the W17 is ready to sail or even before, this impressive Newick 46 will be For Sale and it will be a wonderful boat for anyone dreaming to do what owner Ron had done in his younger days. Write me if you have any interest before its taken .... these Classics are becoming very rare and this one (named 'Slainte', Celtic for Cheers) is a fine example. As Andre and I were in the UK Spring 2024, we had a tour of the boat so we can report she is simple and basic, but Ron kept her light & strong with high quality workmanship, and with the potential to perform at least as well as the original Three Cheers. For me it is an honor to know that Ron selected to build a W17 after owning such a boat... as he knows just what works for a performance, vice-free trimaran. He says he is also eager to build & experience the carbon-fiber Waters WingMast (Mk.l).

====s=====================================================================================

"New articles, comments and references will be added periodically as new questions are answered and other info comes in relative to this subject, so you're invited to revisit and participate." —webmaster.